|

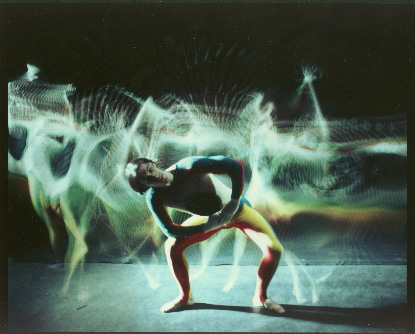

Dance is shape, space, time, and motion. Dance is the movement of a leaf blowing down the street, the rush of

water in a mountain stream, the passing of two strangers on a street, and the ever-changing positions of the planets in the sky. Dance is physical communication. Dance is the art of motion.

Motion is the very fabric of life. It must obey the laws of physics. (Those very laws are both the dancers friend

and enemy.) Dance is both a visceral and personal art. The dance that this course is concerning itself with is

the human form of dance. The body is the instrument of the art form, in service to the motion. In order to study

dance, it is helpful to break dance into a kind of "who, what, where, when, how, and why". The "who" is easy.

It is you, the student, the doer of the dance. The "what" is the body and it's inherit and possible shapes. The

"where" is space, not just the place, the studio, the stage, but the kind of space. Point, line, volume, and other

variables can define Space. "When" is time. Time is not limited to rhythm or beat or duration. It can include

how fast, how slow, stop, go, pause, resume, impulse, etc. "How" is the specific motional quality. The motion

is the unique property of dance. How that motion is qualified is the basis for the richness and range of the

dance world. The last, "why", is as easy as the first, "who". Your "why" is as personal to you as your name and it can range from faint curiosity to a driving passion.

Dance encompasses a vital world. While this course seeks to lay a foundation in motion, it is important to

know some of the history and importance of dance. I urge you to read as many histories as you can. One can

only speculate on the earliest dancing. Perhaps it was as simple as feeling good to be alive by hopping around.

Since that felt good it became a daily ritual. Much early dance was rooted culturally in ritual. By ritual a dance

could be remembered, repeated and passed from one person to another. Much of what one learns is by imitation. If you see someone move in a certain way that is pleasing, you may try to copy that motion. The

original motivation for the motion may no longer exist. A dance has been born. Motion for the sake of the movement is at the base of all dance.

A quick look at any culture, European, African, Asian, Native American, will include dance as part of its

history. We sometimes forget that folk dancing has cultural and historical roots. The sophistication of these

dances; square dances, round dances, polkas, mazurkas, horas, waltzes, tangos, line dances just to name a few, come from cultural traditions passed from one generation to another. Unlike a verbal heritage that is

written and thereby set, movement traditions have always been passed down by physical imitation. These dances take the characteristics of the dancers and must change according to the abilities of performers. Each

succeeding generation adds and subtracts to the heritage. Dance must reinvent itself in order to remain vital.

The motion that seemed so important to one generation of society becomes old hat to the next. The daring in

one dance seems tame after repeated viewing. Historically, the reverse also applies, what seems daring at one time becomes vulgar and even immoral as the pendulum of society continues its swing.

Modern Dance came out of the same revolution that transfigured the emerging global society of the late

Nineteenth Century. A woman named Isadora Duncan, a woman of powerful emotions and beliefs, was one of the first movement artists to embody that revolution. She often talked of the need for personal freedom,

freedom from the shoes, corsets, and psychological confinements that were part of the ruling attitude in performance dance of the day. While no successful revolution is ever accomplished by one person, Isadora

Duncan stands as the figure from whom much of modern dance can trace its roots. She generated the atmosphere that made it possible for Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn to form Denishawn. Denishawn could be

called the first modern dance company. (I am not counting the "Isadorables", the young women who literally

followed in the footsteps of Duncan.) This company, which at one time included Martha Graham, toured much

of the country, performing works based on "world dance" as seen through the eyes of St. Denis and Shawn. Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, and Hanya Holm, who was from Germany and the

Wigman school, became known by some as the big four of the Modern Dance. Nearly all American dance can trace its roots through these four. Since this is a truncated history at best, I need to add that there were many

other influences. I hope that all of you read several histories of Modern Dance to get an idea of what this emerging dance form was like and how it got to the place it is now. The disciples of these four were the major

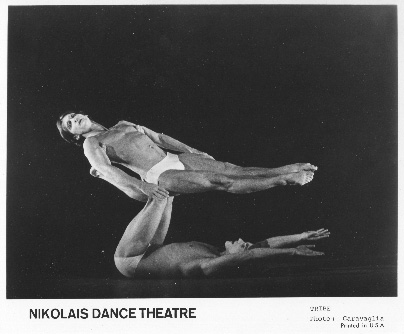

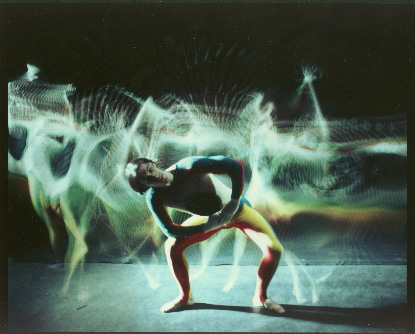

artists of the "golden age" of the NEA Dance Touring Program from the late sixties to the early eighties,

Graham, Cunningham, Nikolais, Paul Taylor, Alvin Ailey, José Limon, and on another level Muller, Primas, Lewitsky, and Falco just to name a few.

Each company, choreographer, and director had a unique vision of dance. This is what sustains the art form

and keeps it vital. Those visions rested on a foundation in motion that was learned and refined in the dance

studio. It is possible to learn a great deal about dance by reading and watching. However, only by serious and

long term physical work can that knowledge be transformed into a useful artistic and communicative medium.

Classes, Week One

- 1. The first class is an introduction of the teacher and the students to each other. The class outline will be handed out

and discussed. The general expectations for the term will be enumerated. Moving will be limited to the simplest walking, skipping, hopping, jumping, running, and etceteras.

Communication, getting a feel for one another will be the prime goal.

- 2. This class will be devoted to simple, gestural movement, including learning to watch one another, the value and pitfalls

of imitation, direct motion, and general vocabulary that the teacher intends on using throughout the term.

TWO: THE WARM-UP

Why warm-up

What should the warm-up accomplish

Class division: floor work, center standing, and across the floor

Specific warm-up

Classes, Week Two

- 1. The warming of the body before strenuous movement is an important part of learning how to dance. The warm-up

accomplishes several things. First, it must warm the muscles and increase the heart rate. Second, it should increase

the mind/body communication. Third, the warm-up increases both stretch and strength to the dancer. Finally, the

warm-up creates specific discipline to the learning process. Accomplished dancers will have learned the proper way

to warm their bodies for class and performance, but young dancers need to have very specific routines taught to them.

As they mature, they can eliminate unnecessary stretches and add exercises to address specific weakness or

problems. During this second week a warm-up developed jointly by Hanya Holm, Joe Pilatis, and Alwin Nikolais will be taught and used for the rest of the semester.

- 2. The plié is an essential part of dance vocabulary. In this class we will continue learning the warm-up and then

move on to the plié, addressing how it is familiar and how it will differ from other classes. Each class in the beginning

weeks will end with some simple exercises of directional walking, running, and leaping. There will be time to ask

questions about the first two weeks of class at the end of this period. If students have questions, the earlier they are addressed the sooner we can move on to more complex ideas.

THREE: THE BODY AS AN INSTRUMENT

Torso, limbs joints and what they can do

Coordination and isolation

Focus

Classes, Week Three

- 1. Since the body is the instrument that the dancer uses to perform her/his art, it is essential to be able to consciously

address the parts that make up the body. This class is a study in body parts and how to show them to an observer.

This class also discusses the importance of dance as a performing art. What you do must be seen. It is not enough to

think that you are doing something, an observer must actually see it. Body alignment will be emphasized in pliés and other standing work.

- 2. Using a specific part of the body to lead the action of the body is one way of motivating motion. In the previous

class one learned where the hand is. Now it is possible for that hand to do something, or the leg, or the head, the

elbow, the shoulder. Leading action with a part of the body is one possibility. Focusing action is another technique

that the performing dancer needs to master. It is always necessary to ask oneself what is the audience seeing.

FOUR: SHAPE

Shape as sculpture

Agreement of shape

Uses of Shape

Shape as gestalt

Classes, Week Four

- 1. The shape or form of the body is an integral part of what we recognize as dance. Just as an athlete must learn a

specific form to successfully accomplish an athletic endeavor, the dancer must form the body exactly to the motional

idea in order to communicate to an audience. Beginning in pliés, the class will make adjustments to exact shapes that

are necessary to a correct vertical piston-like action when descending and ascending. During the across the floor

exercises, particular attention will be paid to learning specific shapes and a method for going from one shape to another.

- 2. While the first class in shape dealt with a solo figure, shape is more often seen from the perspective of the audience

with two or more dancers creating the shape. Learning to hold a shape while locomoting across the floor and

interacting with other dancers at the same time is an integral part of learning how to dance. Today's class will depart

from the usual regular lines across the floor. Changing patterns of locomotion will mix the lines and influence successive lines. Shape becomes clearer as one learns that it can be fluid as well as purely sculptural.

FIVE: SPACE AS DIRECTION

Presence in space

Forward, backward, etc.

Gesture directionally

Up, down

How to use space

Space is something more than a place to kick your leg

Classes, Week Five

- 1. Rudolf von Laban's influence in dance is most notable as his dance notation system has gained wider usage. His

creation of the body tetrahedron has helped dancers to understand space from the perspective of the body and not

just from a position in the room. This class will concentrate on four directions in space: forward, backward, sideward

left, and sideward right. Understanding the relationships of these directions can assist in increased mobility and

balance. Center of the floor work will add the "two-step", an exercise primarily designed for the feet but using eight directions in space.

- 2. Today's class continues directions, adding the four diagonals. In plié, the idea that up and down are also directions

will be emphasized. With the addition of around the corner to the right and around the corner to the left, the twelve

cardinal directions will be addressed. To show an audience where you as a dancer are going, you must command the

space around you and take that space with you. A presence in space that is recognizable to a viewer will enhance every gesture. As the dancer gains command of directions in space that presence will also grow.

SIX: SPACE AS LINE

Making space real (visualization of space)

Point to line to infinite space

Drawing in space

Line and the body

Line and relationships (more than one body)

Classes, Week, Six

- 1. In many of the classical dance schools that began during the last of the 19th Century, mime was taught as part of

the curriculum. One of the reasons was the use of mine in order to advance the story of the ballet. Another, perhaps

more important reason was to teach the dancer how to focus where the audience looks and what the audience sees. We continue spatial concepts this week beginning with one-dimensional space, a dot, and moving on to two

dimensions, a line. The act of drawing a line in space and making it real for the viewer not only makes the dancer more articulate and precise but increases the ability to focus the action to specific gestures.

- 3. The plane of action in any given dance is often a powerful part of how the dance is performed. Still working in

two-dimensional space, forming planes of action affects the whole body. Today's class includes more drawing in

space but adds planar space, including tilted and vertical planes. The end of the class will introduce low, medium and high space.

SEVEN: SPACE AS VOLUME

Creating volumes confined by reach

Defining volume beyond reach

Recognition of existing volumes

Volume and relationships

Classes, Week Seven

- 1. Just as we have defined a dot, a line, and a

circle, we can define three-dimensional space as well. Perhaps the simplest form is a ball. With examples that go from small to large,

using first the hands and then the whole body, it is possible to build three-demsional space that can enhance our

visibility and to limit its movement potential. The space of the stage ceases to be just a place to move in but becomes a defined architectural environment.

- 2. The dancers will make a ball that is defined by the surface of the body. This defined space can then be manipulated

as they locomote through space. Having the responsibility for an imaginary space in relation to other dancers is a

valuable skill. This class is a big step in getting the dancer to focus outside of the self in order to communicate more effectively.

EIGHT: TIME AS RHYTHM

Defining time and its uses

Rhythm, body rhythms and musical rhythms

Patterns of time

Classes, Week Eight

- 1. Stepping on the beat is a primary recognition of time. In this class the 'when' of stepping and how it is shown to the

viewer is the goal. Just as being present in space was important, being present in time is equally important. Special

attention will be paid to the exact moment of weight placement, working on eliminating the early or late attack of a

simple beat. Counting is important. Also, using the body to show beat even when not stepping has real value.

- 2. On the beat, off the beat introduces rhythm as a part of time. Just as the dancer must know when the downbeat of

the rhythm occurs, they must be able to show it to the audience as well. Rhythm is not just counting but illuminating for

an audience the course of a phrase. Syncopation is a part of understanding beat and is a good way of knowing the difference between stepping on the beat and stepping off of the beat.

NINE: TIME AS DURATION

How long, how short, how fast or slow

Sensing time beyond rhythm

Phrasing and molding time

Classes, Week Nine

- 1. Time is a huge subject but ephemeral as well. Understanding how long a gesture takes is

one of the most important things a dancer can learn. Succeeding in reaching the hand into the distance and arriving at

a specific moment with the greatest impact on the viewer is the stuff that artists are made. This class will have little or

no beat to gage time with but will instead, rely on the rhythm of the body to determine how long a step or series of

steps will take. Using the simplest of steps and applying an inner rhythm is a very satisfying method of motion.

- 2. Combining the last three classes, the teacher will create a series of steps that has a beginning, middle, and an end.

This kind of time is often referred to as phrasing. Phrasing has three specific forms. One can phrase a single gesture,

a series of steps, a section, and finally, a dance. Using this ability to phrase, the dancer can bring the excitement of

time and it's manipulation to work in any choreography. Understanding time in this way can also help in learning long

dances. It will also add to the dancer's stamina. They learn to use less energy during some sections and more in others.

|

|